This is a story about a dolphin who set herself free from captivity and found her way back to her family.

One of the challenges we have to meet when filing petitions seeking the release of nonhumans who are being held in captivity is that we need somewhere for them to go. In the case of chimpanzees, there are several sanctuaries available, so it’s as much a matter of being able to provide for their long-term care as it is to secure their release.

When it comes to elephants, there are only two sanctuaries in the United States, and neither of them is currently in a position to accept new arrivals. (That may change in the future.) And when it comes to dolphins and whales, we will need to create ocean sanctuaries where they can have a home for life or be rehabilitated in preparation for release.

Not many dolphins have been successfully returned to the wild. But last year, after six years in a disgusting, insanitary pool at a dingy resort in Turkey, two dolphins, Misha and Tom, were successfully rehabilitated by the Born Free Foundation and returned to the Mediterranean.

She escaped through the netting, hung around for a couple of days, and then headed out into the great blue beyond.

And this week we have the very encouraging story of Sampal.

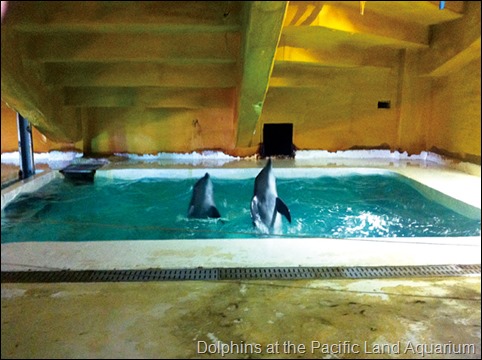

Sampal spent the first 10 years of her life in the ocean around Jeju Island off the coast of South Korea. Accidentally captured in a fishing net, she should have been let go promptly, but was instead sold to the Pacific Land Aquarium, where she spent three years in a tiny underground pool, forced to do tricks for food to entertain customers.

Finally, the Mayor of Seoul stepped in and ordered Sampal and her two pals at the aquarium to be released.

In May, the three dolphins were taken to a sea pen where they could re-learn how to take care of themselves in the ocean. But a month later, part of the netting tore open. Dolphins normally don’t like swimming through small places, but Sampal decided to make a run for it anyway. She escaped through the hole in the netting, hung around outside the sea pen for a couple of days, and then, before her caregivers could figure out how to get her back inside, she headed out into the great blue beyond.

Three days later, Sampal was spotted about 60 miles away, swimming with her own family – a pod of about 50 dolphins. Home and free!

In a post on Take Part, Laura Bridgeman of the Earth Island Institute writes about Sampal:

[Dolphin advocate] Ric O’Barry was not surprised to hear of Sampal faring so well. “I think the others will do fine once they are released, too,” he commented. “They know exactly what to do; they just need the opportunity to do it.”

All too often, dolphins are not given this opportunity. Dolphins represent millions of dollars in annual revenues for any facility, like Pacific Land, that can get their hands on these oceanic beings and manage to keep them alive in captivity. The captivity industry claims that rehabilitation and release projects, such as Sampal’s, are doomed to failure and are dangerous for the dolphins themselves. Some surmise that these concerns are not for the dolphins, however, but for the negative financial impact on companies that profit from exploiting innocent lives.

Certainly, dolphins who were born in captivity are not good candidates for release into an unfamiliar ocean. Nor are those who have been in captivity so long they have no family to go back to and/or have forgotten how to fend for themselves.

But sea pens are a very practical option for dolphins who have spent their lives in captivity but are not suited to the open ocean. And there are hundreds who are in the same category as Sampal from South Korea, and Misha and Tom from Turkey.

At the Nonhuman Rights Project, we look forward to filing suit on behalf of a dolphin and seeing her either returned to her true home and family or given a new home in a sea pen where she can feel the ocean and live a more natural life.