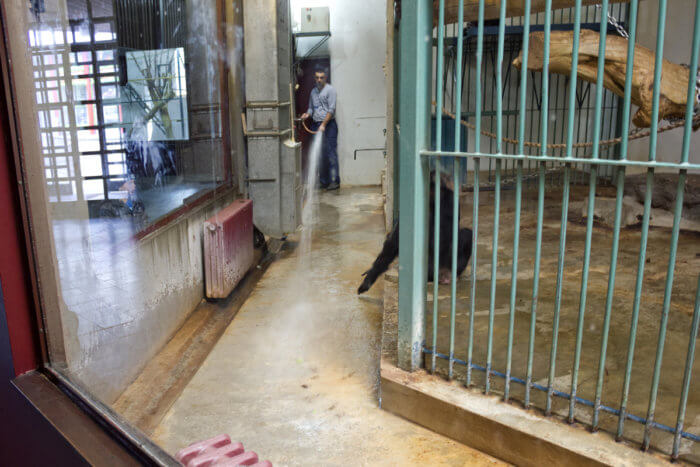

Even as a child I remember being uncomfortable at the zoo. There was something about the foul smell, the stark cement-floor cage, but it was even more about the look of the animals, which I recognized as vacant, sad, and in distress. I couldn’t put it into words at first, but I knew the feelings. Watching the animals chewing on the bars, banging their heads against the wall, pacing back and forth or in circles, I now ask why would anyone want to go to a zoo to see that? I never consciously related to these animals, but their prison-like environment and the whole idea of their incarceration for our entertainment offended me.

I even have a faded memory of a great ape—it was a chimpanzee—masturbating (I didn’t know what that was) and then throwing things out of his cage towards the onlookers. People were laughing, and some mothers were moving their children away—I was confused by that angry and aggressive behavior and again, I experienced an awkward and unclear anxiety from the episode.

In more recent years, in some cases, zoos allow the animals a little more space, along with the ability to be inside or out, and give them plastic toys and props. Sometimes walls are painted or papered with murals of mountains and forests or deserts, and the rocks and trees in their cages are made of cement and plastic. Calling these animal collections a “Wild Animal Park” or “Safari Habitat” may seem like progress, but is it? This notion never ceases to confound me. My husband, Donald Lokuta—the perceptive artist, and I, long ago branded the free spirit, were compelled to act.

We began our curious journey several years ago by visiting zoos on three continents. You may ask why we do this. As photographers, we’re expressing our personal thoughts and feelings; helping others to see more clearly, and hoping to affect social change. We believe that more people might begin to see what we see, and maybe with a little introspection and reflection of our society’s treatment of those we share the planet with, we will move to healthier attitudes and actions.

Although I am still in awe of their beauty and exoticism, and it’s still interesting and thrilling to be able to stand that close to animals I would probably never see “in real life,” there’s still that same gnawing and prickly feeling of guilt, shame, and embarrassment when I witness imprisoned wildlife. The assault of negative feelings hasn’t weakened; it has begun to make me restless and impatient: is the attraction worth the injustice and indignity?

I’ve never been to a marine amusement park. Like land mammals in captivity, sea mammals suffer in captivity, and it disturbs me to think about watching them perform meaningless acrobatic and circus tricks for treats. We understand that they are trainable and can offer this type of entertainment, but is it really enjoyable? If it is, why do we gain pleasure from watching other beings forced to do these meaningless tricks?

“Can’t we, as a society, embrace the idea that wild and exotic animals weren’t put on this planet to live in cages and concrete pens?”

Many years ago, I was in a small Boston Whaler somewhere in the Florida Keys. No other boats or swimmers in sight—just enjoying the warm breeze and drifting along, when out of the blue, my friend and I saw some action in that calm water heading our way. The next thing we knew, we realized that it was a pod of dolphins “standing up” and surrounding us in a full circle. They were clicking and bowing all around us. I felt as if they were curious, greeting us, and asking us to play with them, all at the same time. We weren’t frightened, and it didn’t occur to us that they might have just been looking for food. I think many people have had similar experiences and consequently felt a similar delightful and thrilling sensation…and it stays with you.

Another time, while driving on the Pacific Coast Highway I noticed several cars pulled over and people looking out at the

ocean. When I pulled over to look, I could see a chain of whales moving along—there was no end to this chain; everyone watched in amazement.

Seeing these wild animals in their natural environment was in direct contrast to the feelings I experience while visiting a zoo. Can’t we, as a society, embrace the idea that wild and exotic animals weren’t put on this planet to live in cages and concrete pens? Wouldn’t our children and the rest of society benefit so much more from knowing other living, sentient beings were freed to sanctuaries, rehabilitating from their various injustices? Imagine correcting this grievous mistake and the liberation we’ll all experience from doing the right thing.

About Melissa Tomich